Many people mistakenly believe that the books we read as children have less impact on our personalities than those we read as adults. However, writer Mac Barnett disagrees — in his book “The Secret Door: Why Children’s Books Matter So Much,” he proves the opposite. Forbes Young spoke with book industry professionals, young readers, and psychologists to explore how children’s literature shapes who we become.

The Voluntary Suspension of Disbelief

In “The Secret Door: Why Children’s Books Matter So Much,” published by Alpina Publisher, Mac Barnett challenges the common belief that children’s books are a secondary form of art. He argues that children’s literature is a complete and vital art form — a secret door that opens worlds of imagination, new meanings, and self-discovery. A good children’s book, he says, should not be overly didactic; an author’s task is to tell truthful and engaging stories that broaden children’s perspectives, introduce them to diverse ideas, and help them understand their own emotions. Children’s books nurture thinking and imagination, teach us how to make sense of the world, and shape how we perceive ourselves and others for years to come.

According to Barnett, young readers are both trusting and grateful. The writer says to the reader:

— “I’m going to lie to you now.”

And the reader replies:

— “Great, I’m going to believe you.”

The great English Romantic poet and critic Samuel Coleridge called this the “voluntary suspension of disbelief.” Children, however, simply say “let’s pretend” — and believe.

As Influential as Family

Psychologists believe that the books a child reads influence them just as deeply as their family does. Ideas absorbed from various authors later become part of one’s inner foundation. Clinical psychologist Aliya Sabirzyanova notes: “We usually remember children’s books as bright, warm memories — soft evening light, the voice of a loved one, familiar and beloved characters. But if we lift this nostalgic haze and look deeper, it becomes clear that these stories quietly embed themselves into our psychological core — alongside the influence of family, school, friends, and the world around us.”

Gestalt therapist Valentin Oskin adds that people do not adopt writers’ ideas in their original form — they adapt and integrate them into their own reality. “Of course,” he says, “it can happen otherwise — someone may take what’s written as dogma and fail to think critically about it. That’s understandable, even forgivable, in youth — but for adults, it can be limiting or even harmful.”

Psychologists also warn that children cannot always draw conclusions from what they read and may need adult guidance. Reading, they emphasize, should be voluntary — forced reading often turns young people away from books, which later can manifest as difficulty processing important information in adulthood.

A Reserve of Moves

Valentin Oskin believes that what we read as children influences not only our values and sense of right and wrong but even our future careers. For example, those who loved science fiction often develop project-based imagination, systemic thinking, and an interest in research, while those who preferred classical literature tend to develop refined social skills.

Aliya Sabirzyanova adds: “Children’s books give us a kind of ‘reserve of moves’ — a vocabulary of feelings, examples of decisions, ways of speaking to ourselves and others. We don’t have to use every one of these ‘moves,’ but having them makes us freer — it expands our choices and creates alternatives where there once seemed to be none.”

If the ideas and perceptions formed in childhood no longer serve us as adults, literature can help us reshape them. “Take a piece of paper,” Sabirzyanova suggests, “and write down three to five of your favorite childhood heroes — how they overcame difficulties, treated rules, and achieved their goals. Then list three to five of your recent adult decisions. The similarities are often striking. This isn’t a reason to ‘fix’ yourself, but rather an invitation to renewal: if the old script holds you back, you can rewrite it with new stories, new conversations, and new experiences — from family reading to therapy.”

Forbes Young asked book professionals and young readers how the books they loved in childhood influenced their lives. Their stories show one clear truth: what we read in childhood matters more than anything we may read later.

Artyom Roganov — writer and literary critic

“I found my secret door to the world of literature when someone read and showed me Lidiya Shulgina’s book ‘Come for a Cup of Tea.’ The fairy tale about peculiar animals amazed me with its mystery — I became obsessed with understanding where these strange, intelligent creatures came from, where to find them, and how they related to each other. I began writing down my guesses — right in the book, on the flyleaf, in crooked block letters. I wasn’t even in school yet.

In primary school came ‘The Lord of the Rings,’ the Moomins, and Scandinavian myths — but that first connection happened with Shulgina’s tale. And to this day, I love books that leave a bit of mystery — that give the reader space to imagine and wonder.”

Anna Laur — editor and book reviewer

“The first time I truly immersed myself in a fictional world was in third grade, when I started receiving pocket money. I joyfully spent it all at the bookstore — buying Vladislav Krapivin’s collected works, published by Tsentrpoligraf. I don’t remember why I chose him exactly; probably because Krapivin was from Yekaterinburg, like me, and his books were easy to find on local shelves.

After school, I’d read until evening — ‘The Three from the Carronade Square,’ ‘The Boy with the Sword,’ ‘The Dove Loft on the Yellow Meadow.’ Inside those pages was a childhood so different from mine — a post-war boyhood, poor and hungry, full of sea air and sailor slang. It was a happy kind of childhood, though tinged with the longing of a boy waiting for his mother to return from work, and the sadness of lost friendship. I couldn’t tear myself away from that world.

That was the first time I truly understood what it meant to live another life through a book. It may sound sentimental, but I believe without Krapivin’s books, I would have grown into a completely different person — maybe not better or worse, but certainly different.”

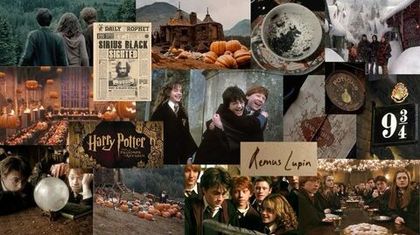

Polina Khodus — student, 21 years old

“Calling ‘Harry Potter’ might sound cliché, but it’s the honest truth. For many people my age, that series was a turning point in developing our sense of identity. The magical Hogwarts, true friendship, first love — these are just a few of the themes the books explore.

What we read in childhood shapes our tastes and interests for life. These books didn’t just entertain; they taught resilience, courage in the face of hardship, responsibility for our actions, loyalty, and the importance of supporting loved ones. I can’t say I’m particularly drawn to fantasy now, but when I revisit ‘Harry Potter’, I often think there’s more realism in it than in some classic novels about ‘real life.’ The characters face fears, make moral choices, and grow through challenges — all of which feel far closer to reality than one might assume.

Perhaps that’s why I’m now drawn to books where fantasy meets deep human themes (hello, magical realism!). Subconsciously, my hand still reaches for stories of adventure, movement, and inner growth. I think it was childhood reading that taught me to look in books not for genre — but for meaning, and for honesty with myself.”